Analyzing a content standard: the Neurobagel Annotation Tool

The assignment

For this assignment, we had to pick an existing institution or collection, and analyze the content standard that they use to catalog resources. We’re supposed to describe its background (its creation, maintenance, governance, etc.) and analyze its strengths and weaknesses.

I chose to analyze the content standard for uploading neuroimaging research data to the Neurobagel platform. For now, I’m focusing on the phenotypic data (e.g., demographics, diagnoses, etc.) and ignoring the imaging data (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging; MRI). This is to keep the scope of this post manageable and to make it easier for my audience to understand.

Background

What is Neurobagel? Neurobagel is “an ecosystem for distributed dataset harmonization and search” (Neurobagel Homepage, n.d.). One of its main features is that it allows you to search for individual research subjects across different neuroimaging datasets. For example, below is a screenshot showing how I would use their query tool to search for data from subjects with Parkinson’s disease who are under 51 years old and have had a specific kind of brain scan (T1-Weighted):

This search returns two datasets, the first with two subjects that match the search criteria, and the second with 12 that match.

They currently have indexed 491 datasets, including 33354 individual subjects.

Who uses Neurobagel? There are two types of ‘users’ of Neurobagel:

- ‘Data-inputters’ (my term): users who want to make their data available on Neurobagel and go through the process of inputting and annotating that data through the Neurobagel Annotation Tool; and

- ‘Data-consumers’ (my term): users who want to find data to use for their research via the Neurobagel Query Tool (shown in the screenshot above).

Origins. Neurobagel was created in 2022 by a group of developers and researchers in the ORIGAMI Lab at the Montreal Neurological Institute, in collaboration with the Douglas Research Center. The primary investigator of the ORIGAMI Lab is Dr. Jean-Baptiste Poline, and the core maintainers are Sebastian Urchs, Arman Jahanpour, and Alyssa Dai.

I did my PhD in the ORIGAMI Lab, and while I frequently heard project updates from the Neurobagel team, I was not directly involved in the project other than occasionally testing their user interfaces.

Maintenance and changes. While the Neurobagel team is primarily responsible for maintaining the software, they welcome contributions from anyone. The software is open-source on GitHub, and they have instructions here for how to contribute through GitHub issues and pull requests.

If someone does not have the time or ability to contribute code to the project, they can also open issues with suggestions or provide feedback via the prompts that pop up as you use their online tools.

How participant data (resources) are input into Neurobagel (resource discovery tool)

The Neurobagel content standard differs from most bibliographic content standards or schemas that I’ve encountered in several ways. I am considering the data for each participant to be a ‘resource’, and participants/resources are embedded within research studies. All participants from a given study probably have the same types of labels, whereas participants from different studies may have different labels. E.g, Study A might collect information about diagnoses of Parkinson’s disease, whereas Study B might collect participants’ scores on an IQ test. Every participant in Study A will have a label of whether or not they have Parkinson’s disease, but they won’t have a label with their IQ score.

You can imagine that there are many (perhaps endless) options for how researchers might label participants, so the system that contains their data has to be very flexible. Not only that, the fact that participants are embedded in studies means that participant data is uploaded in bulk rather than one participant at a time. I’m not sure whether bibliographic catalogers ever catalog items in bulk, but regardless, I doubt it is the norm.

In recognition of these observations, the Neurobagel team has devised a system for uploading and labelling data that is perhaps more complex than most such systems in libraries. The user inputting the data (the ‘data-inputter’) follows these steps:

- Upload their tabular data in a TSV

- Annotate the columns (predicates in RDF), including describing the column, selecting the data type (continuous versus categorical), and labelling it with a standardized variable.

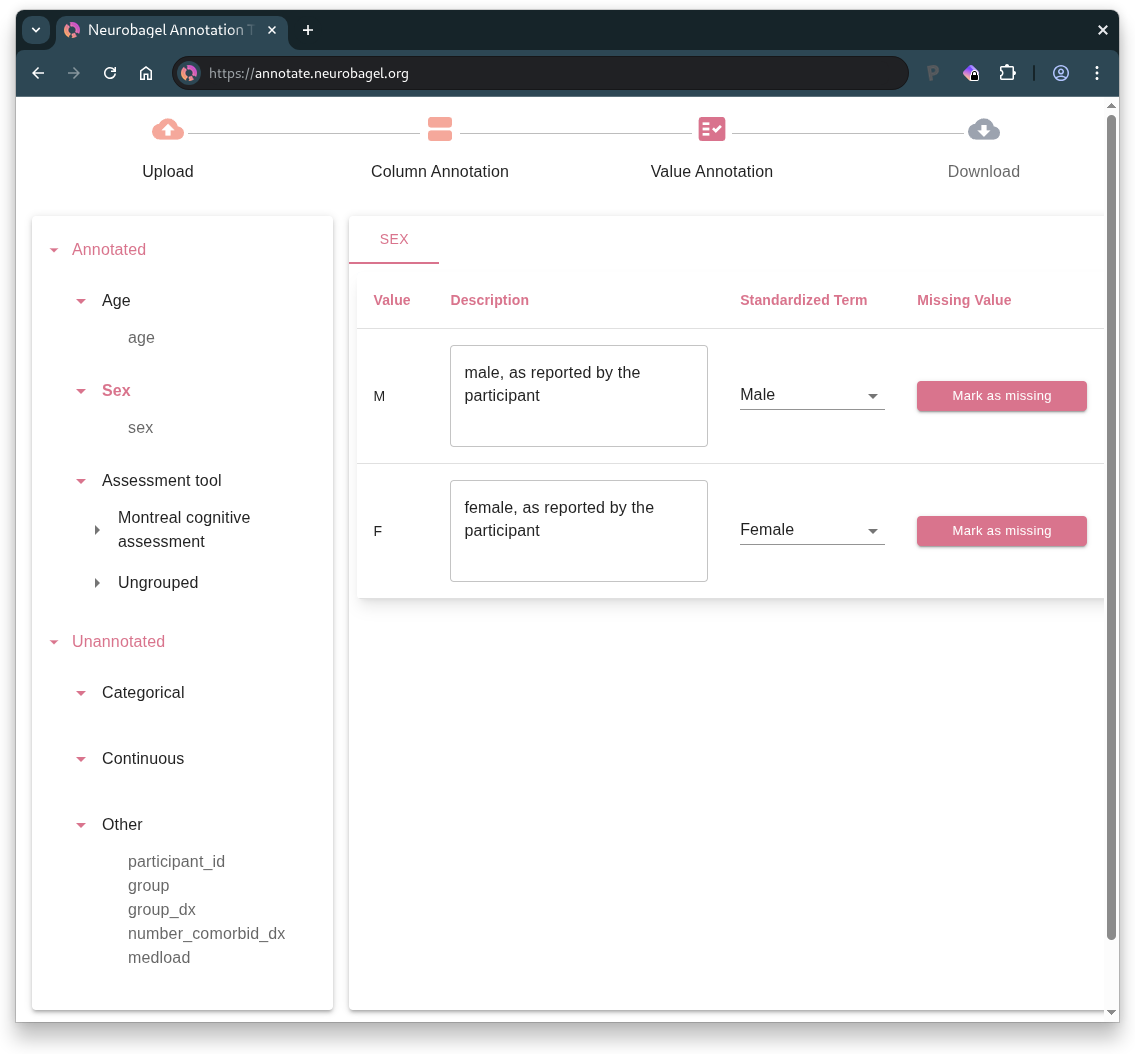

- Annotate specific values (objects in RDF), including describing the value (e.g., “male, as reported by the participant”) and selecting a standardized term (e.g., “Male”) where possible.

For example, this is what it looks like to annotate the value options in a categorical column:

After this process is completed for all columns, the user can download a Neurobagel data dictionary in JSON format. This file contains the specifications for the annotations.

The next step is to run a command to combine the participant TSV with the data dictionary JSON to create the JSON-LD file that is consumed by Neurobagel. This can be accomplished in Python with a specific command that is easy to adapt (Generating Harmonized Subject-Level Metadata - Neurobagel, n.d.):

bagel pheno \ --pheno "Dataset1_pheno.tsv" \ --dictionary "Dataset1_pheno.JSON" \ --name "Dataset 1" \ --portal "https://www.mydatasetportal.org/dataset1" \ --output "Dataset1.JSONld"Analysis of strengths and weaknesses

While the Neurobagel team has tried to make it easy to annotate data with controlled vocabularies, a data-inputter still needs to know how to work with TSV and JSON files, as well as how to run some basic code in a Bash shell (to integrate them into JSON-LD files).

From my perspective, as someone with moderate technical expertise, the process looks straightforward and well-documented. However, based on my experience in the neuroimaging field, I know that many researchers will not have the technical expertise to contribute their data to Neurobagel without learning some new skills and perhaps installing unfamiliar software.

I think the Neurobagel team manages this hurdle by working closely with people/groups who want to contribute data, to guide them through the process. My impression is that the task of adding data to Neurobagel is usually given to someone with more coding/data experience on a given team; it is not necessary for everyone involved in the research or data collection to be able to do this.

References

Generating harmonized subject-level metadata—Neurobagel. (n.d.). Retrieved December 15, 2025, from https://neurobagel.org/user_guide/cli/

Neurobagel Homepage. (n.d.). Neurobagel. Retrieved December 15, 2025, from https://neurobagel.org/

Commentary

Discussion with Neurobagel team

I did not have this assignment ready before I did my presentation to the Neurobagel team. But I did have an idea of the various systems involved, and we discussed aspects of their Annotation Tool. Below are the questions I asked them and my summaries of their answers. I integrated some aspects of this discussion to expand the post above beyond the assignment requirements.

Why make the Annotation Tool rather than a set of guidelines and code to verify the user-created files?

- Most of the components behind Neurobagel already existed (e.g., BIDS, JSON-LD, TSV, graphs). The gap that Neurobagel filled was creating the user-friendly tool for neuroimaging researchers to format and link their data appropriately.

What kinds of issues have come up for people using the Annotation Tool?

- During user tests, people are almost too polite; they seem hesitant to give critical feedback.

- They get better feedback from people who actually need to use the system for their work.

Possible next steps

It is difficult to think about the content standard for Neurobagel because it is so flexible. If I wanted to write this post in a way to help people who want to input their data into Neurobagel, I might go through the Neurobagel Annotation Tool with fake data and make a table with the required attributes (I think there would be too many optional attributes to include them all), so that the content standard looks like a bibliographic content standard. That being said, I’m not sure that the table format that we used in class to create our own small content standards actually resembles most official content standards.